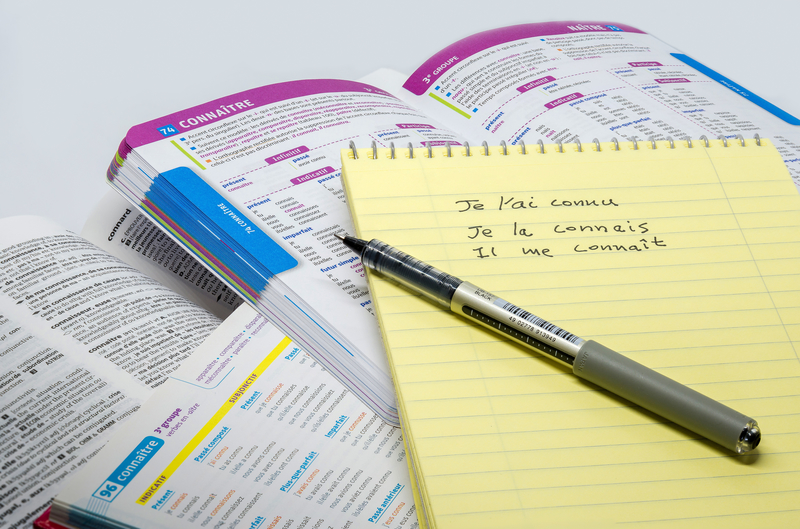

All French verbs end in either -er, -re, or -ir. Each of these verb categories has specific rules governing how they change to express layers of crucial information about the situation. There are many similarities between English verbs and French verbs, but, if you’re like most native speakers, you don’t usually consider what tense a verb is in, whether it has an irregular conjugation, if it is reflexive, in its infinitive form, etc. You just use the form of the verb which communicates the specific information you wish to express.

The goal is to get you to the same level of fluency with your second (or third, etc.) language, where you avoid existential moments (Am I speaking? Who am I speaking to? Is it reciprocal? Did this action have a specific ending point in the past? Would it be considered habitual?) and simply speak French without a second thought.

To arrive at that point, you have to become aware of all the nitty-gritty grammatical features of your own language, so that you can begin to translate the meaning you wish to express into the available grammatical structures of your foreign language. In this guide, we will bring your attention to a few basic verb-related concepts which exist in both English and French.

The importance of verbs cannot be understated in the endeavor of fluency. One little word can express so much about a situation, completely changing the meaning. For example, the difference between “I would like to eat some cake” and “I ate some cake” is striking. All that changed was one little constituent – the verb (from conditional tense to past tense, if you’re curious). So, while memorizing vocabulary is an extremely important exercise when learning a language, if you’re not aware of how to use the verbs you learn appropriately, you’ll be extremely limited in what you’re able to say.

How French Verbs Change

The form of a verb changes to show who perpetrated the action (the person) and when it occurred (the tense). Verbs can also change according to categorizations called “moods,” which are similar to tense. Rather than helping you express when something happened, mood allows a speaker to express their attitude toward a subject. Some examples of mood in French are indicative, imperative (used to give commands), conditional (used to express possibility), and subjunctive (used to talk about opinions and desires).

French uses one extra category of person (vous) that corresponds to addressing “you all / you guys” in English.

French personal pronouns

| je = I | nous = we |

| tu = you | vous = you all / you guys |

| il/elle/on = he (masc.) / she (fem.) / we (informal) | ils/elles = they (masc.) / they (fem.) |

Though native speakers may not notice it, English verbs also change depending on who performs the action and when it occurs. Most verbs only change in the third person singular (see below) in English, but all verbs change to distinguish when something occurs.

| Person (Singular) | Present tense | Past tense |

|---|---|---|

| First person | I walk | I walked |

| Second person | You walk | You walked |

| Third person | He/She walks | He/She walked |

In most cases (apart from irregular verbs), the English past tense is formed by adding -ed to the word. Whereas English verbs don’t change much in either spoken or written form, French verbs are often pronounced the same but change drastically in written form. For this reason, native French-speaking children devote hours in primary school to learning conjugation charts to be able to properly spell the many forms of verbs. Like you, they probably never realized that French verbs change their forms until this unfortunate surprise!

Both English and French have a lot of irregular verbs which simply need to be memorized, but learning the rule for regular verbs makes conjugation much easier. Generally, irregular verbs are some of the most common verbs in the language because historically their forms have fossilized, rather than evolving to match new patterns in the language (since they’re just used so much!).

Being exposed to verbs in context (rather than just in a chart) is also crucial to becoming comfortable using them – not to mention it’s more fun! Use Lingvist’s French course to see verbs in context as well as look over grammar tips to clarify concepts explicitly as needed.

Never Change! Finite Verbs That Stay the Same

Infinitifs

The infinitive form of a verb is its most basic form. You can spot them easily in French because they retain their original ending of -er, -ir, or -re. The equivalent meaning in English is the same as “to [verb],” so aimer translates to “to like.”

Except when stacking two verbs together (“She [likes] [to run]” / “Elle [aime] [courir]”), the infinitive form needs to be adjusted to express the who and when. This is where conjugation comes in. For regular verbs, the infinitive lends its stem to its conjugated forms in a predictable way. The stem, or radical (from “root” in French: racine), is the part that occurs before the -er, -ir, or -re.

Participles

The other type of verb that doesn’t change its form includes the present and past participles. You will mainly encounter the past participle, which is used in conjunction with an auxiliary verb to form the passé composé. The passé composé (literally “composite past,” but technically perfect tense) is a form of the past tense used for an action that had a specific ending point. This is in contrast to the imparfait (imperfect), which is used for habitual actions or actions that have a fuzzier end point. As participles are combined with another inflected (a.k.a. conjugated to reflect person/tense) verb, they don’t need to change their form. Most past participles are formed by adding an -é, -i, or -u to the stem of the verb for -er, -ir, and -re verbs, respectively. There are, of course, irregularities in participle forms as well.

Example: “to love”

- infinitive: aimer

- past participle: aimé

- present participle: aimant

Exception: Certain participles do need to be adjusted to reflect the gender of the subject (main noun) of the sentence.

Auxiliary Verbs

Auxiliary verbs (or “helping verbs”) are used to support a certain form of a verb but don’t contribute any semantic meaning to the compound form. In English, common auxiliary verbs are “have” and “be,” as in the sentences “I have written two letters” or “I am sleeping.” In these sentences, “have” and “be” don’t really express their dictionary meaning, but instead help define the tense of the main verbs “to write” and “to sleep.” The verbs avoir (to have) and être (to be) function very similarly in French. Every verb is “assigned” one or the other auxiliary verb to form the passé composé, with just a few exceptions, in which choosing an alternate auxiliary changes the meaning. See if you can spot the auxiliary verb in the example for both the imparfait and the passé composé, which we discussed in the previous section.

J’avais dix ans quand j’ai goûté l’escargot pour la première fois.

I was [no specific end point since an age lasts a year = imparfait] ten years old when I tried escargot for the first time [passé composé].

Though they don’t express exactly the same meaning, the use of the auxiliary “have” and the past participle “given” are very similar to as donné.

Être

Present tense: être (to be)

| je suis | nous sommes |

| tu es | vous êtes |

| il/elle/on est | ils/elles sont |

Past Participle: été

Avoir

Present tense: avoir (to have)

| j’ai | nous avons |

| tu as | vous avez |

| il/elle/on a | ils/elles ont |

Past participle: eu

Hopefully the comparison of these concepts in English and French will help you get started with changing verbs to fit your intended meaning. French grammar can certainly seem overwhelming, but knowing the English equivalents can help you navigate the stormy sea of verbs. For more guidance on verbs and exercises to practice conjugations, sign up for Lingvist’s French course today!