So you’ve already learned the basics of talking about love and romance in French. Now you’d like to take it to the next level and understand how to speak and write vividly about matters of the heart.

They say that one of the best ways to learn a complex art form is to first imitate the masters; once the rules of the game are second nature, you can start to break them. So let’s explore the love letters and poetry of some of the great French-speaking writers.

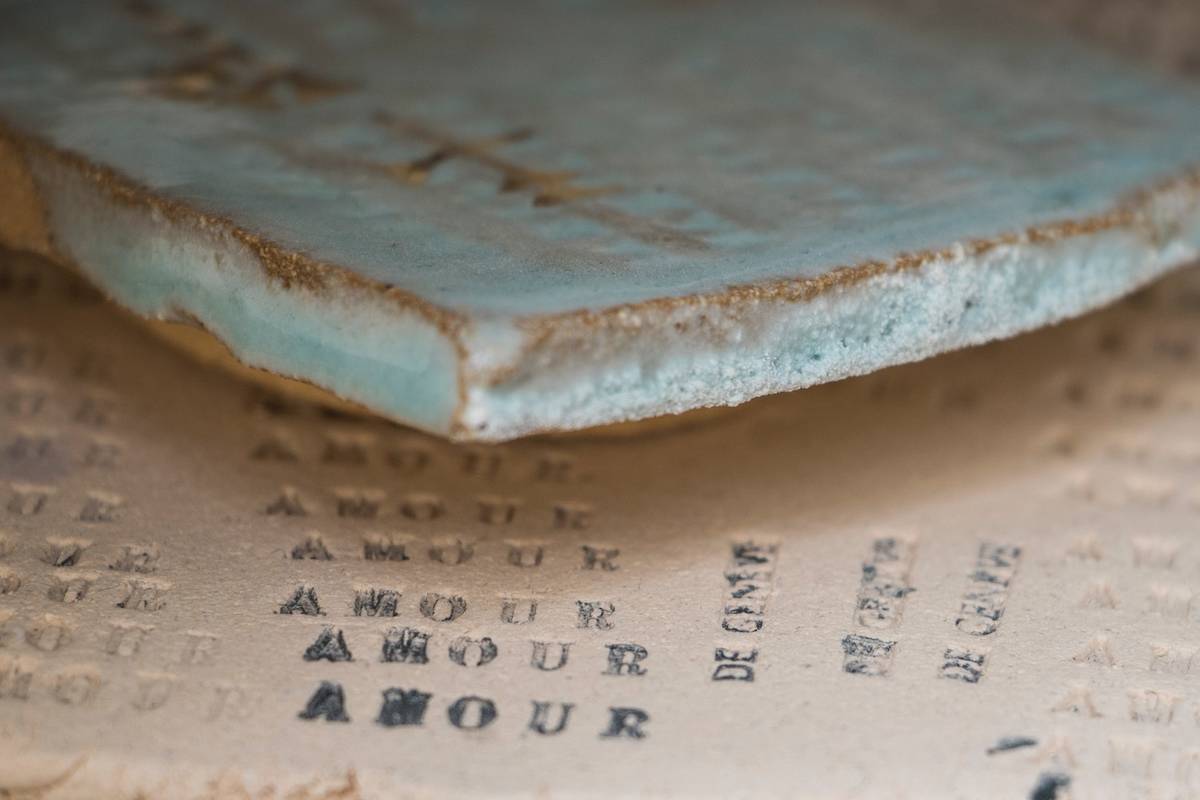

French Love Quotes

Let’s start with some short-form texts to get you thinking like a true romantic.

“Amour veut tout sans nombre, amour n’a point de loi.”

– Pierre de Ronsard

Les amours (1552-1578)

De Ronsard was known as the “prince des poètes et poète des princes.” He found his inspiration in the Greek and Latin classics, and as a result he is seen as a major contributor to the renaissance in France.

“L’amour est l’emblème de l’éternité, il confond toute la notion de temps, efface toute la mémoire d’un commencement, toute la crainte d’une extrémité.”

– Germaine de Staël

Corinne ou l’Italie, 1807

Germaine de Staël wrote extensively and deeply about both love and politics. One of her contemporaries remarked that “there are three great powers struggling against Napoleon for the soul of Europe: England, Russia, and Madame de Staël.”

Once Napoleon cemented his power, he exiled her for 10 years. During this time she traveled all over Europe, developing her ideas along with her network, ultimately leaving an enormous mark on history.

“Oh ! si tu pouvais lire dans mon coeur, tu verrais la place où je t’ai mise !”

— Gustave Flaubert

Correspondance, 6 August 1846

Flaubert’s writing is known for being perfectionist in terms of style and aesthetics. He aimed to represent his subject matter as realistically as possible, avoiding speculation or magical thinking.

Despite this, he considered himself to be one of the romantics. Even after realism fell out of fashion, writers continued to admire and emulate him.

Nabokov said that he “paved the way towards a slower and more introspective manner of writing,” while James Wood remarked that his style “maintains an unsentimental composure and knows how to withdraw, like a good valet, from superfluous commentary.”

There are many lessons here for writing a beautiful French love letter, or indeed any type of letter, for that matter.

“Le seul vrai langage au monde est un baiser.”

— Alfred de Musset

Poésies nouvelles: Idylle, 1836-1852

Alfred de Musset was a Parisian poet, playwright, and novelist who lived in the first half of the 19th century. He was a divisive figure in his day, with some of his contemporaries openly disapproving of his work.

Much of his most romantic writing is said to have been inspired by his love for the novelist George Sand. The intimate letters they wrote to each other are considered to be an important artifact of the cultural heritage of France.

“Rien n’est petit dans l’amour. Ceux qui attendent les grandes occasions pour prouver leur tendresse ne savent pas aimer.”

– Laure Conan

Angéline de Montbrun, 1882

Marie-Louise-Félicité Angers was a Quebecois writer who used the pen name Laure Conan. She is considered one of the pioneers of the “psychological novel.”

Laure Conan’s work is some of the most notable to emerge from the École Patriotique de Québec, a group with religious views on the destiny of French Canada, who mostly rejected the modern and romantic ideas coming out of post-revolutionary France.

“Car, vois-tu, chaque jour je t’aime davantage, aujourd’hui plus qu’hier et bien moins que demain.”

— Rosemonde Gérard

L’éternelle chanson, 1889

Louise-Rose-Étiennette Gérard was a poet and playwright. She wrote these lines as part of a poem to her fellow writer Edmond Rostand, and the next year they were married. The poem became popular almost two decades later, when a jeweler started engraving these lines on medallions, an idea that was copied all over France in various formats and variations – similar to “Keep calm and carry on” in English.

“Je vous aime avec quelque tragique et tout éperdument.”

— Simone De Beauvoir,

Letter to Sartre, September 1938

For the existentialist philosophers, love wasn’t all about “happily ever after.” They didn’t shy away from talking about pain, tragedy, or even confusion in their feelings. But they weren’t coldly rational either, often describing their experiences with intense language.

Beauvoir and Sartre famously had an intense and complicated relationship. They aimed for what they saw as “authentic love,” requiring that the two lovers retained their individuality and acknowledged their differences.

“Aimer, ce n’est pas se regarder l’un l’autre, c’est regarder ensemble dans la même direction.”

— Antoine de St-Exupéry,

Terre des Hommes, 1939

Antoine de St-Exupéry is well known internationally for his novella The Little Prince. In the early 20th century, he became one of the first pilots to take airmail, flying between France and various destinations in Africa, and later in South America.

He disappeared during the Second World War, while flying a reconnaissance mission over occupied France. His wife Consuelo immediately began writing their love story, The Tale of the Rose. She sealed it away, and it was discovered after her death and published decades later.

“C’est cela l’amour, tout donner, tout sacrifier sans espoir de retour.”

– Albert Camus

Les Justes, 1949

Camus was an Algerian-born French novelist who was one of the principal architects of the philosophy of Absurdism. He believed that true freedom is found when the human defines their own meaning and purpose. One must “live without appeal,” rejecting both despair and leaps of faith.

“Quand on est aimé on ne doute de rien. Quand on aime, on doute de tout.”

— Colette

(1873–1954)

Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette was a mime, actress, journalist, and novelist, most active in the salons of Paris at the turn of the century. She continued to write even in the 1940s.

“Je viens du ciel et les étoiles entre elles ne parlent que de toi.”

– Francis Cabrel

Petite Marie, 1977

Francis Cabrel is one of France’s most celebrated singer-songwriters. He’s heavily influenced by Bob Dylan, and often fuses elements of folk, country, and blues with the traditional creative tools of chanson francaise.

This line comes from Petite Marie, a song that he wrote for Mariette Darjo, and used to win the competition that would launch his career. The pair were married that same year.

Improve your French language skills

French Love Poems

Knowing how to turn a beautiful phrase in French is a great start.

But a great love letter is more than just a sequence of beautiful statements. There has to be an inner composition, an order and unity to the overall piece. In order to learn that, let’s examine some poetry.

Les amoureux

L’eau qui caresse le rivage, La rose qui s’ouvre au zéphir, Le vent qui rit sous le feuillage, Tout dit qu’aimer est un plaisir.

De deux amants l’égale flamme Sait doublement les rendre heureux. Les indifférents n’ont qu’une âme ; Mais lorsqu’on aime, on en a deux.

-Madeleine de Scudéry (1607-1701)

Extract from Amphitryon

L’attente d’un retour ardemment désiré Donne à tous les instants une longueur extrême, Et l’absence de ce qu’on aime, Quelque peu qu’elle dure, a toujours trop duré.

-Molière (1622 - 1673)

Les roses de Saâdi

J’ai voulu ce matin te rapporter des roses ; Mais j’en avais tant pris dans mes ceintures closes Que les nœuds trop serrés n’ont pu les contenir.

Les nœuds ont éclaté. Les roses envolées Dans le vent, à la mer s’en sont toutes allées. Elles ont suivi l’eau pour ne plus revenir ;

La vague en a paru rouge et comme enflammée. Ce soir, ma robe encore en est tout embaumée… Respires-en sur moi l’odorant souvenir.

-Marceline Desbordes-Valmore (1786 – 1859)

Extract from Cyrano de Bergerac

Un baiser, mais à tout prendre, qu’est-ce? Un serment fait d’un peu plus près, une promesse Plus précise, un aveu qui peut se confirmer, Un point rose qu’on met sur l’i du verbe aimer; C’est un secret qui prend la bouche pour oreille, Un instant d’infini qui fait un bruit d’abeille, Une communion ayant un goût de fleur, Une façon d’un peu se respirer le coeur, Et d’un peu se goûter au bord des lèvres, l’âme!

-Edmond Rostand (1868 – 1918)

Ready To Send Your Own French Love Letter?

It’s time for some advanced French writing practice.

This exercise is straightforward. Think of the person you love, and imagine what you’d say to them if you were a hopeless romantic living in Paris in the 19th century. Don’t worry – you don’t have to actually give them the letter if you don’t want to. But maybe if you hold onto it you’ll feel like giving it to them months or even years later.

Now what does it take to write a great love letter? Read the work of the great French writers closely, and think about the subtle effects of their choice of words. Ask yourself if there might be another meaning besides what’s on the surface, or if the same general meaning could be conveyed with a different emotional character. That’s the technique component.

But writing love letters is about more than technique. Before you put pen to paper, you have to examine your own feelings and intentions. When you think you know what you want to write, ask yourself why that and not something slightly different? The best love letters don’t rely on cleverness as much as they rely on boldness and vulnerability.

Experiment with starting sentences in different ways: with an infinitive verb first, an indefinite article, an adverb or pronoun. Mix up very short sentences and longer ones. Aim to say less, as though you expect your reader to finish your thought for you.

How To Write an Address in French

How about posting your letter to a real amour who lives in France?

We’ll have to get the French letter format right, or at least the address.

The way to write an address in French is as follows:

[Title]. [Names] [LAST NAME]

[Secondary address information, e.g., apartment number] – if necessary

[Access information, e.g., entrance location] – if necessary

[Street name and number]

[Lieu-dit] – smallest place name for rural addresses, if necessary

[Postcode and relevant locality, e.g., the city name]

[Country] – if international

The customary greetings for informal French letters typically use a form of the adjective cher. There are a few options here:

- Cher Monsieur [last name]

- Chère Mademoiselle [last name]

- Cher/Chère [first name]

- Mon Cher / Ma Chère [first name]

- Mon/Ma très Cher/Chère [first name]

- Mon Chéri / Ma Chérie

As for closing expressions, you might use:

- Affectueusement

- À bientôt !

- Bisous / Bisoux

But you can also get creative.

Improving your French writing skills

For one thing, practice makes perfect.

Exercises like this can help you think about how to express yourself in French and give you a sense of ownership of the language. In other words, it will help you feel less “foreign” when you communicate in French.

But it’s also true that with a limited vocabulary, you might not be able to express your thoughts and feelings with the same level of precision as in your native language.

Doing 50 to 100 Lingvist cards per day at least four days a week is a super-effective way to expand your vocabulary. In combination with natural communication, your French skills are sure to improve rapidly – and you’ll be writing beautiful and amorous discourses in no time.